ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN THE DAILY MIRROR ON 07.02.24 BY NADA FARHOUD ENVIRONMENT EDITOR

Retail giants like Amazon and Apple have been criticised for not taking enough action against electrical goods ending up in landfill, so "fixperts" have waged a war.

What do you do when your TV stops working or the food processor goes on the blink? Chances are you take it to the tip and buy a new one.

The UK is the world’s second largest producer of electrical and electronic equipment waste, with half a billion items going to landfill each year. By the end of the year, we are expected to top this wasteful table.

It is estimated that each household chucks out £800 worth of electrical goods each year, nearly half of which ends up straight in landfill.

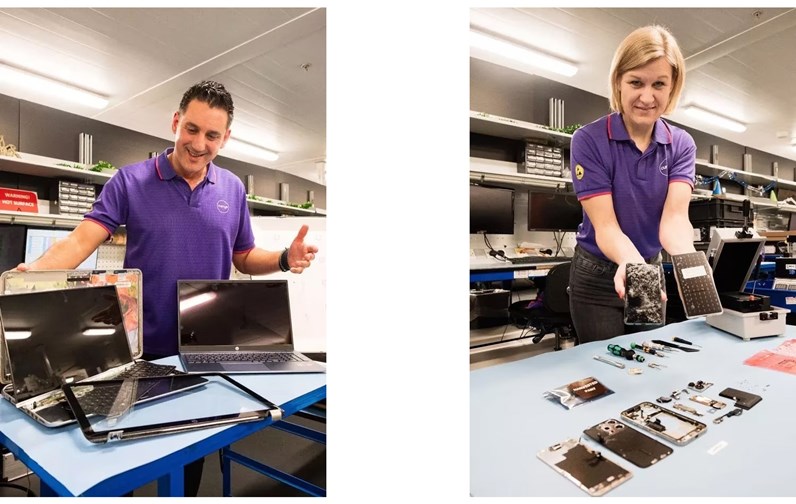

But now thanks to a growing number of “fixperts”, the UK is beginning to wage a war on throwaway culture. Not only is it better for the planet but buying a refurbished item is better for your pocket too, with potential savings in the hundreds. While some retailers such as Amazon and Apple have been criticised for not taking enough action, Curry’s repair lab is now the biggest in Europe. I visited it to find out more about how broken technology can be saved from the mountain of waste.

Almost three million products pass through these doors each year to be repaired, refurbished or recycled. Millions of spare parts are also kept in a library, to ensure many more items can be fixed in the future.

David Rosenberg, service operations director, is leading the fight against our throwaway culture. He tells me: “We know that e-waste is a challenge, so whilst we believe in the benefits that new technology can bring, we know that we can’t just continuously buy new and not think about what we do with our existing, or older items.”

As we walk around the 500,000 sqft warehouse in Newark, Nottinghamshire, he explains that there is value in any old technology, even an old laptop gathering dust at the back of a cupboard.

David adds: “All the components are incredibly useful as they can be harvested for parts so we can repair other similar products. Or it might be able to be repaired. That’s why we always encourage our customers to trade in or recycle their old tech.” For parts that are hard to track down, a cutting-edge 3D printer is used to replicate them.

While I was there, a switch for a broken vacuum cleaner was being made. A demonstration in the television section shows that, rather than replacing a whole screen, it’s possible to just replace smaller broken bars.

David explains that before this technology was available, many older products could not be fixed. But in 2022 the repair lab carried out more than 800,000 individual repairs.

He says: “The idea that tech is disposable has gone. We believe in the mindset of nothing is going to waste.” Customers are given a £5 store voucher when they bring in any old tech to be reused or recycled, through Currys’ Cash for Trash scheme.

Currys either strips out the reusable parts, dusts off and resells the item or donates it to a charity. The average UK household owns approximately 25 electronic devices. Around 20% of electronic devices in the UK are hoarded or stored in households.

In 2020 alone, the UK generated approximately 24.9 million discarded mobile phones. The recycling of one million mobile phones can recover approximately 16 tonnes of copper, 350 kilograms of silver, 34 kilograms of gold, and 15 kilograms of palladium. The average age of a kettle in the UK is 4-5 years.

It is not just major retailers who are helping to stop items ending up in landfill. The Share and Repair shop in Bath, Somerset, is one example of a community helping its residents by “reducing, repairing and reusing”.

The first pop-up cafe was born in 2017 after founder Lorna Montgomery, 66, struggled to mend her kettle. She says: “My next door neighbour, who is now one of our repairmen, looked at the kettle and said, ‘Oh if only I had a tool, I could mend that.’ Little did I know four and a half years later, we would be here with a shop.”

With only the two part-time general managers listed as employees, the charity relies on its army of 150 volunteers. France has gone one step further by paying a “repair bonus” to those who fix a broken shoe, rip in their trousers or replace missing shirt buttons. Since October, people have been able to claim back €7 (£6) of the cost of mending a heel and up to €25 (£21.40) for clothing repairs done by sewing workshops and cobblers that have joined the scheme.

It has been modelled on France’s “repair bonus” for household electrical goods. There is no equivalent to the French scheme in Britain yet.

But Austria offers one, as does the German state of Thuringia and the US city of Portland, Oregon – so a repairing revolution could be just around the corner for us too.

All photos © Reach Commissioned. Photographer: Paul Drabble